We love Errol Morris and Polaroids. Just had to have Michael Masterson review this super new doc. Treat yourself!

By Michael Masterson

When I was a teenager I wanted a Polaroid SX-70 camera so badly I could taste it. When my parents finally caved in and gave me one for Christmas, I was entranced with the magic of instant photography. However my artistic ambitions were immediately limited because the film and flash bars were so expensive for a kid. Each print was precious.

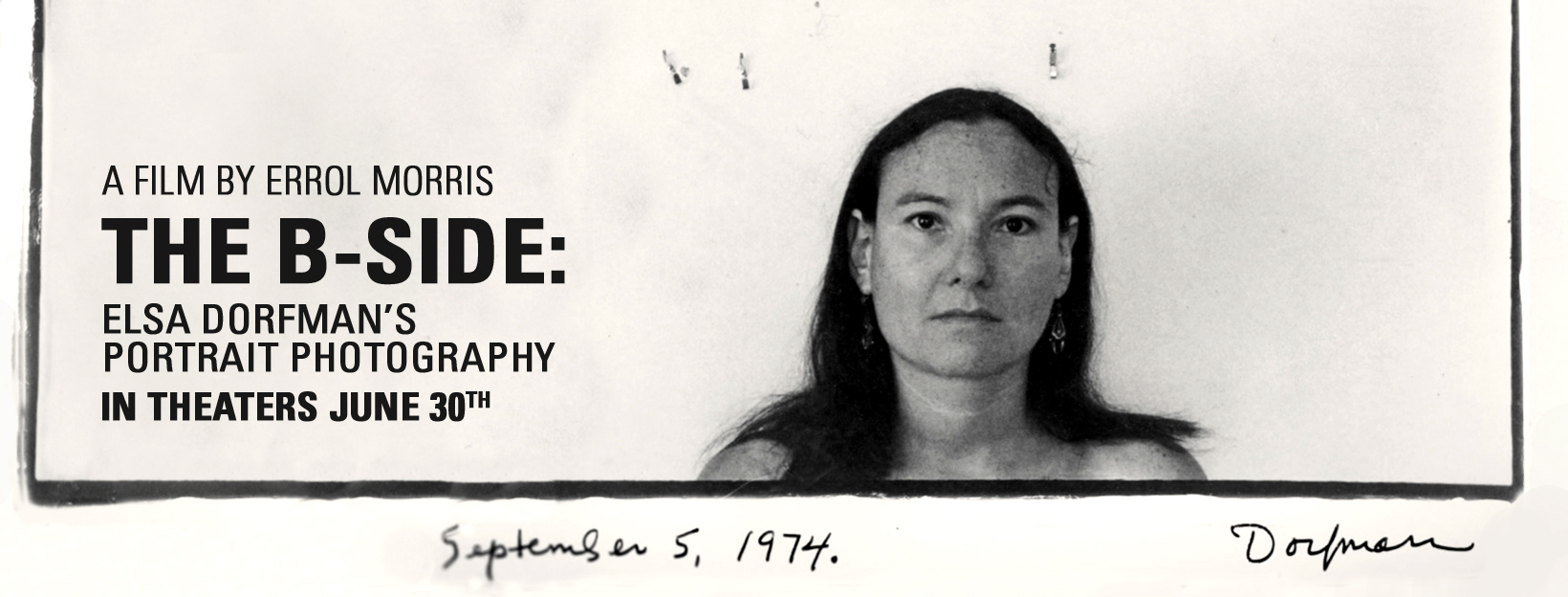

In Errol Morris’s “The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman’s Portrait Photography” we find out that this renowned Polaroid portraitist always had to pay for her own film too. One can imagine how costly 20 x 24” Polaroid film is and it explains the title. She usually only took two photos using the large format camera, letting the client choose one and keeping the other for herself like the B-side of a 45-rpm record. The film walks us through Dorfman’s life as Morris chats with her and she pulls photo after photo from stacks of flat files including many photos she hasn’t seen herself for decades.

From the moment you first see Dorfman onscreen you love her warmth and authenticity. It’s like watching an old friend reminisce. A series of random encounters and events shaped her and a career that would have been unlikely for a “nice Jewish girl from Boston” in the 50s. Dorfman’s life is as much as a woman’s story as an artist’s journey. From an era when women were expected to marry and stay home with their family, she bucks the system repeatedly discarding the expectations of her parents and society.

After college she got a job at the Grove Press in New York mostly making copies laboriously in the pre-Xerox era for authors who came in needing manuscripts duplicated. Among them was Alan Ginsberg who became a lifelong friend and frequent portrait subject. After tiring of New York, she moved back home and took a teaching job. It was not a good fit. A parent even tells her she doesn’t really belong there.

But by chance a program at MIT was using photographers to document teachers and the one assigned to her nonchalantly gave her a Hasselblad telling her she could be a Berenice Abbot. The idea that she could be a photographer stunned her. As she says, the only thing people had ever said she could be was a “jerk.” But in reality, she’d always been an artist without a means to express herself until she found photography. She started by taking portraits of authors like Robert Lowell, Ann Sexton and Jorge Luis Borges at Grolier’s bookstore in Boston, becoming comfortable with the medium and in particular capturing moments of herself and her home life. She gathered these images in “Elsa’s Housebook – A Woman’s Photojournal” in 1974, a landmark book for photography and a female artist.

Dorfman was an outlier, living with the man (lawyer Harvey Silverglate) who became her lifelong companion and later husband, peddling her photographs for two bucks each in Harvard Square armed with a letter from Harvey to show police that she had the right to do so. At one point she discovers that Polaroid has built five 20 x 24” large format Polaroid cameras that they only rented to a small select group of photographers. Determined to join them she “nags” the company endlessly and when one comes back from Japan, Polaroid capitulates and rents it to her on the condition she provide a proper studio for it. The cost of renting the camera, the studio and the film itself result in her becoming a portrait photographer to pay the bills.

Each giant Polaroid tells a story and forms a flashback of over 30 years of hairstyles and fashions as well as poignant memories. On the white frame below each print she writes a caption and dates it. In one self-portrait she’s standing holding a photo of her parents. On the bottom she’s written that it was taken the day after her father died. It’s one she hasn’t seen in years and she sobs quietly. I did too. You see her ageing gracefully through many self-portraits, often taken with her husband and son. Their closeness is palpable.

You also see Ginsberg throughout the many years of their friendship. He loved having his picture taken she tells us, frequently nude. The first time he shows up at her studio naked she’s completely flustered, a nice Jewish girl not used to seeing other men’s privates. But after all, it’s Alan and she forges ahead. One memorable later shot is a photo-within-a-photo. Dorfman also occasionally had access to a 40 x 80” camera and a black and white print that size of Ginsberg in a suit and tie hangs on the wall. He stands before it naked, fixing the camera with a piercing gaze. She then shows us the next shot: she’s joined him and while his expression is the same, she looks like she’s at a sleepover with her best friend.

At one point she confesses that she had to fight for everything with Polaroid. Even after achieving a modicum of fame she had to pay for every piece of film; they never gave her a single package. Even among the select few photographers allowed access to the large-scale cameras, she was always at the bottom. I suspect it’s because she was a portrait photographer for hire, not thought of as an artist or commercial success. She minimizes her own abilities, saying that the camera is just a fork or spoon, not the soup. She laments the demise of Polaroid and condemns its buyers who discarded the machinery and other irreplaceable artifacts.

Dorfman looks at one image and says it’s “great” then immediately becomes self-effacing saying it’s just like calling your child great. Of course he is and so is the picture. Morris asks her if her images capture real life. She shakes her head no, asking how could it be real life. I disagree. Her images are more than just real life; they are outsized moments of wonder and delight.

The site where you can learn more and find a screening:

http://bsidefilm.com

Michael Masterson has a broad range of experience in marketing, business development, strategic planning, contact negotiations and recruiting in the photography, graphic design and publishing industries. In addition to his long experience at the Workbook and Workbookstock, Masterson owned and was creative director of his own graphic design firm for several years. Masterson has been a speaker or panelist at industry events such as Seybold, PhotoPlus Expo, Visual Connections and the Picture Archive Council of America (PACA) national conference. He is past national president of the American Society of Picture Professionals (ASPP). He currently heads Masterson Consulting, working on projects ranging from business development for creative companies and sourcing talent for them to promoting and marketing industry events as well as providing resume and professional profile services for job-seekers. He can be reached at michaeldmasterson@gmail.com.

Michael Masterson has a broad range of experience in marketing, business development, strategic planning, contact negotiations and recruiting in the photography, graphic design and publishing industries. In addition to his long experience at the Workbook and Workbookstock, Masterson owned and was creative director of his own graphic design firm for several years. Masterson has been a speaker or panelist at industry events such as Seybold, PhotoPlus Expo, Visual Connections and the Picture Archive Council of America (PACA) national conference. He is past national president of the American Society of Picture Professionals (ASPP). He currently heads Masterson Consulting, working on projects ranging from business development for creative companies and sourcing talent for them to promoting and marketing industry events as well as providing resume and professional profile services for job-seekers. He can be reached at michaeldmasterson@gmail.com.